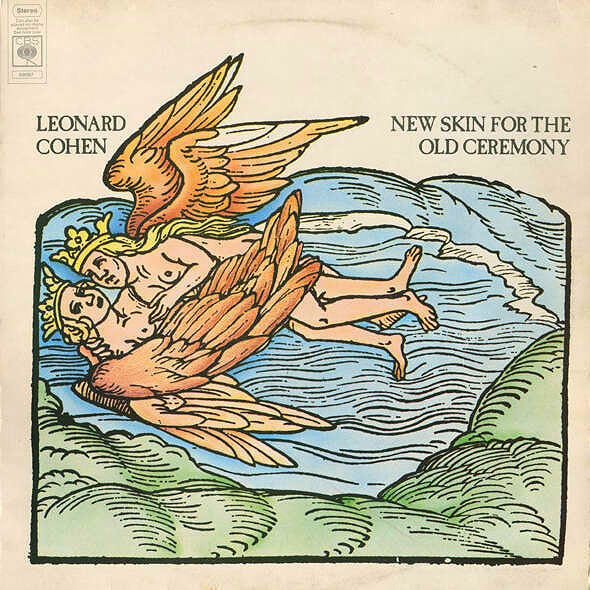

LEONARD COHEN: NEW SKIN FOR THE OLD CEREMONY

ALBUM REVIEW: Leonard Cohen's fourth LP, shockingly, rarely makes a top-tier appearance in lists of his greatest work. It's insanity! I also remain unconvinced that he was that miserable...

LEONARD COHEN: NEW SKIN FOR THE OLD CEREMONY

COLUMBIA/CBS RECORDS

1974

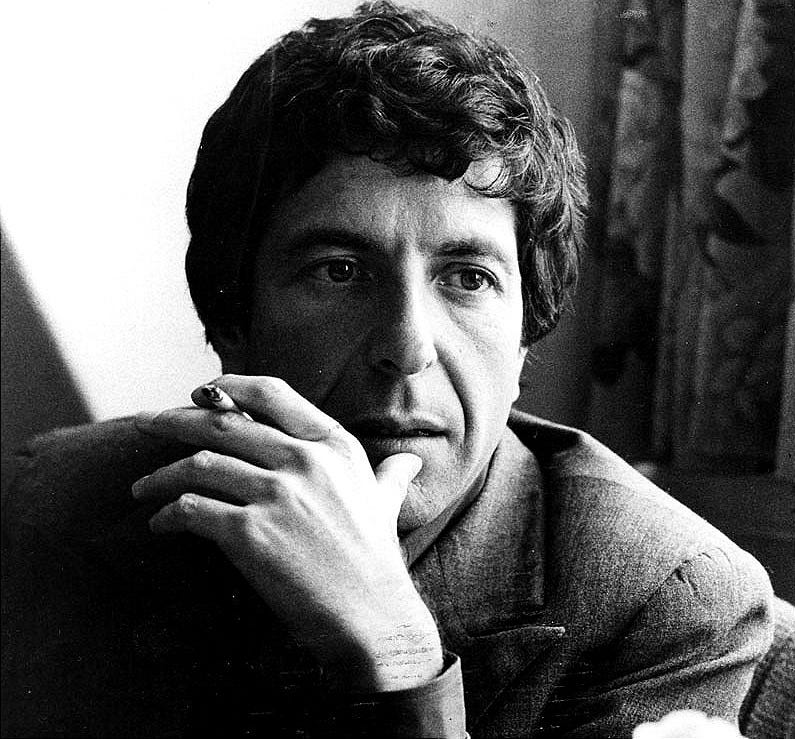

It’s too easy to dismiss Leonard Cohen as the Marquis of Miserablism. That seems, in my experience, to be the default response of a listener that doesn’t buy into his artistry.

Yet.

For they will.

It makes me sad, because those (dis)missives are too easy and are entirely missing the point of the wry, dour humour which proliferates through so many of his songs - especially from New Skin for the Old Ceremony onwards.

I respectfully request that those who (thus far) don’t adore him, re-frame the “misery” to “sarcastic and self-deprecating jousts between his true self and how he sees himself”.

Think Larry David more than Oizys.

The mild jocularity inherent in his perfect poetry must surely be fueled by the Jewish blood that ran through his veins. There’s something unique to the tone of David, Sarah Silverman, Lenny Bruce, Mel Brooks, Woody Allen et al, that shares an ancestral kinship and character with the best of Leonard Cohen’s work and wordsmithery.

It’s so fucking articulate and carefully constructed. Understated. Never played for gags. He’s no clown - but the situational irony, the disappointment and amusement inherent in life, is where his eye excels at picking out the detail, while his shaving mirror reflects it back at him in his first-person poems.

That’s what you miss if you disregard Cohen’s work too easily. And it’s a mistake to do that. Leonard Cohen has the (almost) unique ability to gift the listener with an entirely new way of viewing the world. With modesty, amusing futility and joyous resignation.

It’s a way of life.

Those who know, just know.

It’s why you rarely meet a casual Cohen fan; once you get it, you can’t help but go all-in.

Even in the depths of the despondency that curates his most despairing work, his lyrical genius conjures a vision that breaks that veil of despair.

In his own words; all things have a crack in them - it’s how the light gets in. The crack in Cohen’s darkness is the humour. It’s what creates a textural depth. It breaks the monotony of misery and lends his words more power.

I am thinking of Dress Rehearsal Rag, from the midst of the despondency of Songs of Love and Hate. It’s a poem of self-reflection both literally and metaphorically. Amidst a shave, he muses:

“Cover up your face with soap there, now you’re Santa Claus

And you’ve got a gift for anyone who will give you his applause

I thought you were a racing man but you couldn’t take the pace

That’s a funeral in the mirror and it’s stopping at your face.”

The bone dry self loathing is bordering on hilarity.

Or take one of his most well known songs, from his second LP, 1969’s Songs From A Room - Bird On The Wire:

“Like a bird on the wire;

Like a drunk in a midnight choir -

I will try, in my way, to be free.”

Those three lines paint a timeless picture - like a tragi-comic postcard relaying the subtleties of atonal chaos at an inebriated Midnight Mass - the freedom of naivety. The drunk doesn’t know he’s out of tune or causing a disturbance; he’s just free. Enjoying the moment.

It’s a beautiful thing.

It reminds me of a Victorian cartoon; the horrified look on the faces of the congregation. The rosy-nosed innocence of the drunkard’s sincere gusto as he bawdily spins an empty wine bottle around his head, dancing clumsily down the aisle towards the pulpit.

Or, if you still don’t believe me, take mid-period highlight, Tower of Song. It contains one of my favourite Cohen lines of all time, delivered with a deliberately flat tone that exemplifies his critical reputation for tuneless sprechgesang:

“I was born like this, I had no choice

I was born with the gift of a golden voice.”

Dripping in sarcasm, I find it laugh-out-loud funny.

Much like Blixa Bargeld says of Einstürzende Neubauten’s reputation for straight-faced, Teutonic Brutalism: “Never underestimate the humour in Neubauten.”

Bearing that in mind, immediately, the pandemic cooking shows that Blixa broadcast are as relevant a part of his overall artistic oeuvre as Halber Mensch is.

That specific comment was made in response to the lyrics of Pestalozzi, an early track on Rampen, their newest LP, in which an arcane list of ingredients is recited, from Bamboo Skewers and Quail’s Egg Scissors to Nuclear-strength Perfume and a Cellar Full of Noise.

On first listen it sounds like a recipe for some dismal ritual magick.

The truth is, it’s the list of items that he had bought on Amazon over the preceding months.

All of which is to say, don’t underestimate the artistry behind Cohen’s lyric writing, either.

If it all really was just tuneless misery, as first-glancers would have you believe, he wouldn’t have achieved a body of work so timeless it will outlast all of us.

There’s not a person reading this, whose lifespan won’t be dwarfed by First We Take Manhattan.

He doesn’t write comedy songs - leave that to Chas ‘n’ Dave - but his writing has far more light and shade than is apparent at first glance - or that he is ever given credit for.

My inciting moment was in the early 1990s.

I picked up New Skin For The Old Ceremony at a Record and Tape Exchange in London’s Notting Hill.

I was interested adjacently, because of the inspiration Cohen had imbued in the Sisters of Mercy. I came via the path of references from the Bad Seeds, Tindersticks and other post-goth wonders.

I knew no songs, but it was cheap, tatty, and I liked the artwork. Little did I know that that casual purchase would lead me to a lifelong love - enough to give my only child Cohen as a middle name.

I’ve still got that wretched, taped up and peeling copy of the LP.

I love its clicks and crackles almost as much as I love the songs themselves.

The spare recording is a great way to contrast the compression of CDs with the air of a vinyl pressing. In latter years, I had become so used to the digital version, that when I played the record, I was amazed to hear a long-forgotten cello so low in the background mix of Chelsea Hotel as to be almost inaudible - and certainly almost unnoticeable on the completely compressed CD version I had.

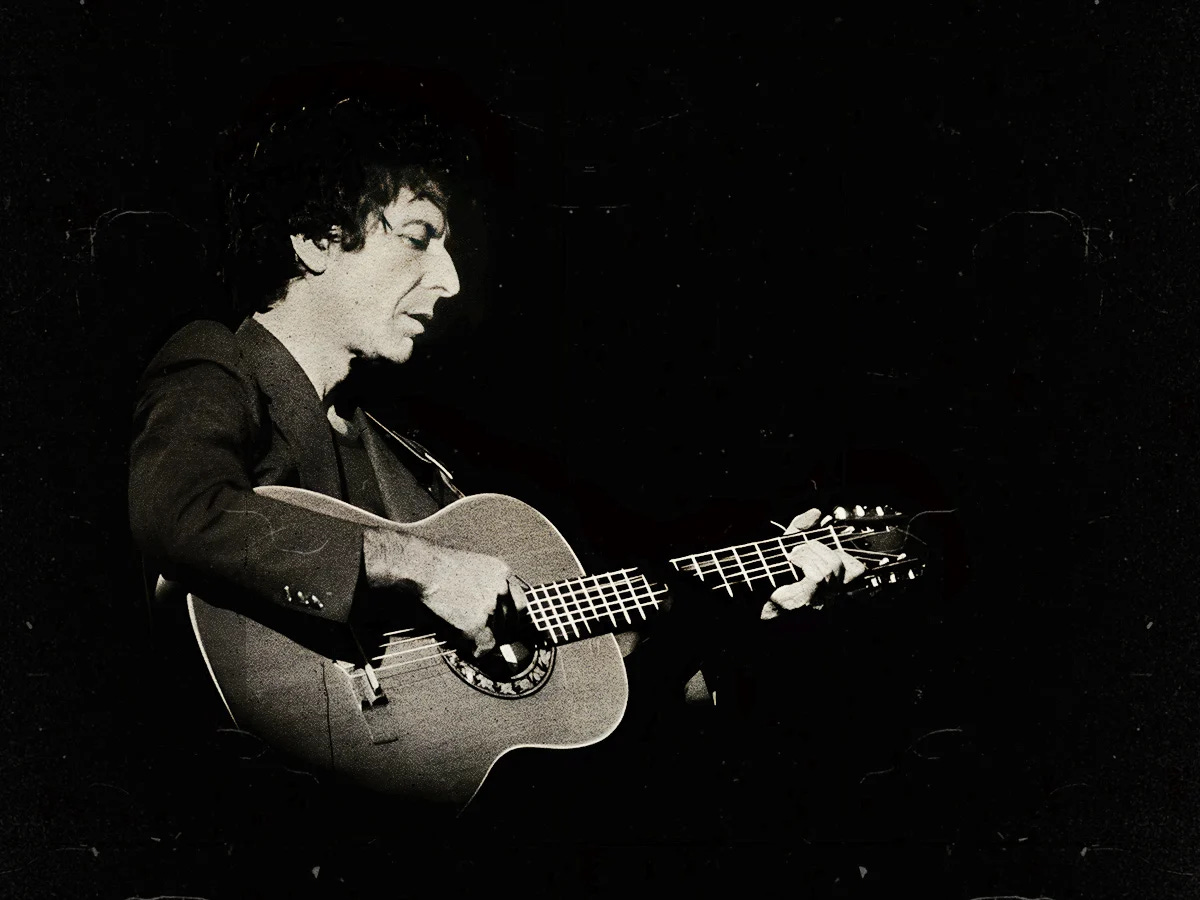

There’s a wonderful space to the sound of New Skin. It’s really the first time more orchestration is brought into his writing. It’s a long way from lush, but previous albums had only sparse instrumentation, where now we get more strings and traditional folk/rock accompaniment. It’s a long way from the Casio keyboards of the 1980s that would obsess our hero. It’s still a firmly acoustic sound, but it’s a coherent move forward, lyrically and instrumentally, from the first three albums.

New Skin For The Old Ceremony is Leonard Cohen’s fourth album. It surprises me that it rarely breaches the top three of his best albums in those lists that perpetuate across the interwebs.

I am here to make the case for it being his best work, most consistent LP and greatest recording.

So burn me.

Who By Fire? Why, me, Sir.

Light the blue touchpaper.

See if I care.

Upon release, New Skin for the Old Ceremony was met with a somewhat cool response. The first three albums had all done really well, but New Skin didn’t even trouble the Billboard 200. In the UK, things were different; it went Silver over here, but all the same, the first three albums had performed better.

Perhaps people were expecting more darkness - certainly, Songs of Love and Hate, the preceding LP, still counts as Cohen’s most dimly lit masterpiece in most listener’s opinions. The by-comparison levity of New Skin was perhaps not leaning into that expectation far enough? It was a specific direction agreed upon between Cohen and the LP’s producer, John Lissauer - to be a bit lighter.

Maybe that strategy didn’t work so well with the fanbase at the time.

“I think it (Songs of Love and Hate) was gloomy because it was shrouded in loneliness. Leonard and I shrouded New Skin in ‘Let’s not be so serious.’

We tried to make it listenable, and I don’t want to say ‘entertaining,’ because we didn’t go for hit-making. We [wanted to] make it illustrated. I wanted to help drape these songs in a nice frame and make a vignette or something.”

John Lissauer, Tidal.com, 2019.

I refuse to believe the album’s lack of traction had anything to do with the quality of the songwriting and must have had more to do with the mood of the audience.

Fifty years on, and New Skin for the Old Ceremony has been voted number 22 in Rolling Stone’s Best 74 Albums of 1974.

“Though it’s now regarded as a fan favorite, New Skin for the Old Ceremony was the first Leonard Cohen album that failed to crack the Billboard 200 chart. It received lukewarm reviews, with critics describing the John Lissauer co-production as “overproduced” and “not one of his best”.

But time has been kind to this bohemian masterpiece, and though there are far more instruments on here than on his previous releases — including banjo, mandolin, and woodwinds — it remains chillingly sparse and romantic.”

Angie Martoccio, Rolling Stone, 2024.

Fair warning: the article that follows will quote heavily from the lyrics of the songs. Every track is an impeccable example of brilliant lyric writing, elegantly contained within its musical walls.

Events begin with multi-instrument shuffle of Is This What You Wanted, with it’s oddly slow and disjointed funky chorus. We hear the boing of a Jew’s Harp, the lull of a tuba (or some other low brass) and the impressive bass of either John Miller or Don Payne - impossible to tell which - but its calm, sparsely driven rhythm rolls the song away awkwardly and beautifully.

Lyrically, we’re firmly in love-gone-wrong territory. Unrequited, of course. Throughout, the song lists all the grandiose things that Leonard’s lover was - followed by the cheap, unsuccessful compliment that was his role.

She is KY Jelly. He is Vaseline.

She is Jesus Christ, he is the Money Lender.

She is the manual orgasm; he is the dirty little boy…

And then, the last verse turns things on their head; Leonard retains his youth as his fanciful lover wears herself out. In this kitchen sink tale of hare and tortoise, his patience and lack of ambition is the one constant. Her adventures are the disruptor to their balance.

But ultimately, he’s just glad she’s there. He ignores her misdemeanours, and carries on regardless.

That last line is magical and wraps up a long term relationship in a single simple utterance.

“You got old and wrinkled; I stayed seventeen

You lusted after so many, I stayed here with one

You defied your solitude, I came through alone

You said you could never love me… I undid your gown”.

The immaculate Chelsea Hotel #2 comes next.

Famously admitting to its muse being Janis Joplin, the lyrics tell of a fellated tryst in a bedroom of the famous fleapit for artists and musicians on Manhattan’s West 23rd Street.

Even more famously, Cohen regretted declaring who the song was about and apologised long afterwards, to Janis’ ghost, admitting to his indiscretion and feeling guilty about it.

To my ears, it’s the perfect entry-level Cohen song. I’ve introduced people to his majesty many times, using it as such. It’s a simple song with beautiful, sad words of a lost moment, but with the wry acknowledgment that ultimately, the conquest - for both of them - is just one of many more to come.

That magical self-deprecation and hid delusions of grandeur are particularly profound in the second verse:

“I remember you well in the Chelsea Hotel;

You were famous, your heart was a legend.

You told me again, you preferred handsome men,

But for me, you would make an exception.

And clenching your fist, for the ones like us

Who are opressed by the figures of beauty,

You checked yourself and said “Well nevermind -

We are ugly, but we have the music…”

And then, dismsmissed with the clinching final half-verse:

“I don’t mean to suggest that I loved you the best;

I can’t keep track of each fallen robin.

I remember you well in the Chelsea Hotel…

That’s all - I don’t think of you that often.”

The fact that he puts himself in the Alpha position as the one who vocally treats their liason flippantly, when we know that really, that rare erotic moment plays on his mind all the time, has a wry self awareness that shares its quiet amusement with the listener.

The thrumming flamenco feel to Lover Lover Lover brings an image of a fiery latin relationship to mind - and the bass playing, once again, does a marvelous job of immersing you into the world that Leonard is creating.

The main riff has a slide in it that you can’t help miming to when it inspires you to take an exotic two-step around the living room. It’s also an earworm that wriggles and writhes for days.

There’s a line that makes me smirk, despite it not intending to be fanciful:

“Then let me start again, I cried.

Please let me start again.

I want a face that’s fair this time.

A spirit that is calm…”

Leonard’s having a conversation with God, bickering about what his purpose is and how he is physically ill-equipped to deal with life’s challenges.

What makes me smirk is my mis-reading of “fair” in the second line. I assume it’s intended to be fair - as in delicate and beautiful - but I always heard it as being a complaint against the unfair hand he was dealt - with his normal, boring features.

I like my version the best.

Field Commander Cohen is a gripping fantasy about an ancestor of Leonard’s, in which he himself plays the role of a soldier - or our ‘most important spy; parachuting acid into diplomatic cocktail parties…’.

It’s a firm favourite of mine. It’s righteous march and stiff pace echo the lyrical content perfectly. The lines worth quoting here are less humourous, and more profound - partly because of their delivery - but when he sings, I shiver:

“I know you need your sleep now

I know your life’s been hard

But many men are falling

Where you promised to stand guard…”

It’s a statement on exhaustion - not just occupational, but emotional.

The air of futility underpins everything, from the tone of the words to their delivery of them.

Importantly, beyond the fantasy, this is a real protest song, acknowledging the pathetic situation that veterans found themselves in, having returned home from (specifically, the Yom Kippur) war to be unsupported, traumatised and suicidal.

He himself had just returned from a brief tour of duty there, lending morale to the troops with his performances.

Why Don’t You Try is a slinky, smooth and mildly lecherous tale about luring a woman away from her partner. Conveyed from the point of view of the ever-supportive, salivating, horny wolf, waiting in the dark for the target of his insidious ‘advice’ to be alone.

A slippery oboe solo confirms the snake-hipped, predatory tempter.

You can see him, in your mind’s eye; a devil, sliding across the dance floor, be-suited, ready to lure his prey into his devious and sinister possession.

There Is A War is another domestic tragedy that aligns the tedium and the ambient locking of horns between a man and a woman as a comparison with global, timeless, religious and final conflict.

“I live here with a woman and a child

The situation makes me kind of nervous

I rise up from her arms she says

I guess you call this love - I call it service.“

The cynicism amuses me. The fact he’s overwhelmed and she’s not - she’s just going through the motions… the futile existence and resignation of both of them accepting their lot is almost passive - not an attitude you automatically associate with war.

Or is it written in retrospect?

An ode to lost love and an empty enticement back to the battleground of domesticity?

A Singer Must Die is up next. It’s a slow waltz revolving around a performer in the dock, being judged for the lies of his words. It’s essentially a railing against critics, his defence being his necessity to write and the endurance of his sexually seductive research to fuels his poetry. It’s not fun, I assure you - it’s work.

He lacks conviction.

“And all the ladies go moist and the judge has no choice

A singer must die for the lie in his voice

And I thank you, I thank you for doing your duty

You keepers of truth, you guardians of beauty

Your vision is right, my vision is wrong

I'm sorry for smudging the air with my song.”

That last line is ace.

There are a couple of moderately forgettable songs on the LP.

I Tried To Leave You is one of them. The melody is not magnetic at all and the lyric is unsubstantial. Steer clear. Along with album closer Leaving Greensleeves, which, despite its impassioned reinvention of the traditional, is ultimately passable, at best.

The LP would be stronger by omitting both songs, ideally replacing them, at least in part, with a studio re-recording of Queen Victoria, which had only appeared as a live song and would have supplemented the tracklist well, despite its more morose tone.

Who By Fire leads us towards the end of the album. Recently covered by PJ Harvey, it’s one of the signature tracks of the album. If you paired it with Chelsea Hotel, you’d get a perfect overview of what the LP was about. The single to support the album instead lead with Lover Lover Lover and Who By Fire was the B-Side, which is a close second best, I suppose.

Who by Fire basically lists ways to die - or situations within which death could occur - questioning who might depart under these circumstances.

It’s more orchestrated than most songs on the LP and provides a late high in the tracklisting.

As we’re ignoring Leaving Greensleeves, the final track is Take This Longing, and it’s a good one - essentially (for me) because of the re-appropriation of its lyrics by Morrissey in The Smiths’ classic Hand In Glove, from 1984:

“And everything depends upon how near you sleep to me…

I’d love to see you naked over there

Especially from the back;

Just take this longing from my tongue

And all the useless things my hands have done

Untie for me your hired blue gown

Like you would do for one you loved.”

It’s another self-deprecating essay on rejection. Cohen is uniquely specific regarding the angle at which he would most enjoy the view; a detail so blunt it’s at once funny, lecherous, complimentary and cheeky.

He loves his role as the Omega underdog more than he would as the Alpha. If he was the triumphant hero of his stories, he would have no tale to tell.

The joy of the words comes from his ineptitude and failure.

Beautiful Losers.

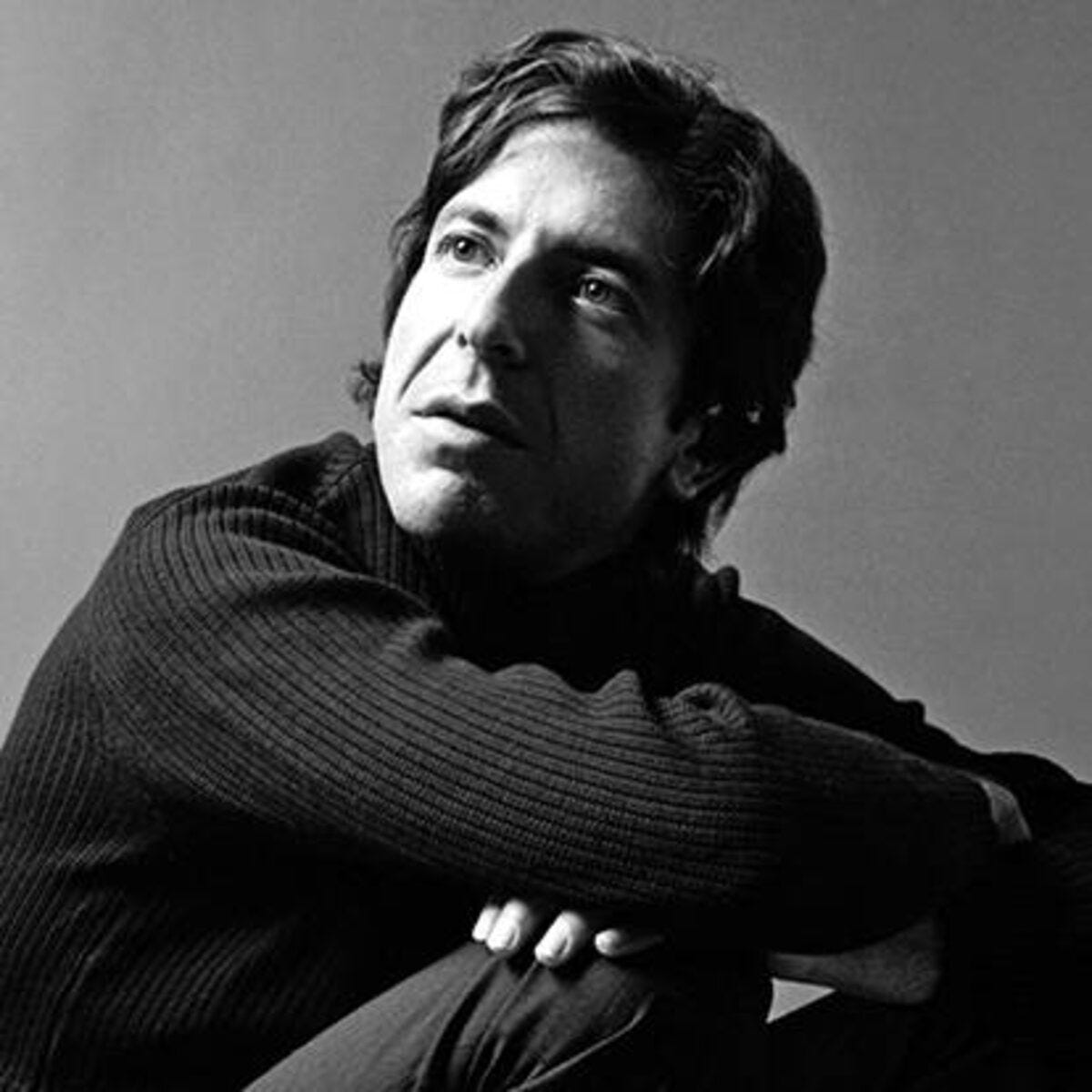

To conclude, there is huge sarcastic depth to the lyricism of New Skin for the Old Ceremony. It’s a step away from the dense morose wall of sadness and regret of his earlier work. The more detailed instrumentation adds further finesse to his relatively simple songs.

For me, this is quintessential Leonard Cohen. That’s not to say you shouldn’t fully bury yourself in his broader catalogue; Songs of Leonard Cohen, Songs of Love and Hate, I’m Your Man, The Future and You Want It Darker, especially, are all magnificent.

Released after his death, Thanks For The Dance is a particularly touching memorial to his skills as a songwriter, storyteller, poet and lyricist. Pick it up if you can.

If you’re already a fan, you’ve already got your favourites. If you’re reading this, naïve to the wonders of the Sad Old Bard of Toronto, you could do much worse than launching your incoming infatuation with New Skin for the Old Ceremony.

Congratulations; you’ve reached the point of true enlightenment.

Ave, Funsters!